Press Releases

December

2023

7

New Research Finds Big Banks Holding City Deposits Guilty of Modern Day Redlining

FOR IMMEDIATE RELASE: December 7, 2023

Contact: Will Spisak, will@neweconomynyc.org

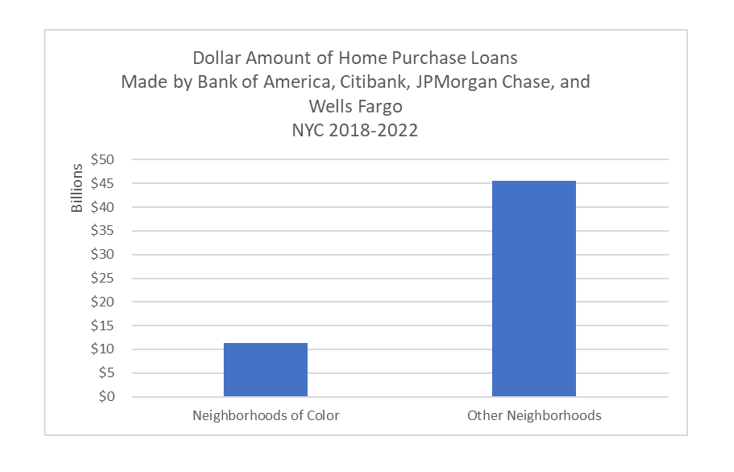

NEW ANALYSIS: Big Banks Holding City Deposits Provided Only 25 Cents in Home Loans in NYC Neighborhoods of Color for Every Dollar Lent in All Other Neighborhoods

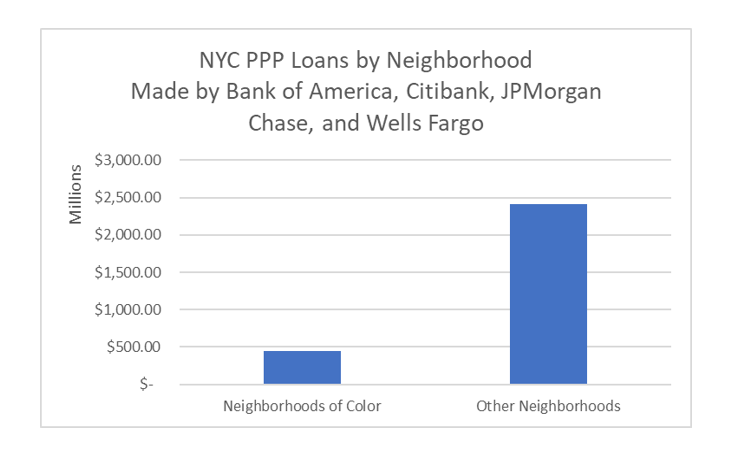

Same Banks Provided Just 19 Cents in PPP Loans to Small Businesses in NYC Neighborhoods of Color for Every PPP Dollar Lent in All Other Neighborhoods

Vast Disparities in Branch Locations Persist

Coalition calls for the creation of a public bank to divest public money from banks that harm communities, and reinvest in community wealth-building and high-quality financial services in neighborhoods of color.

NEW YORK, NY – New Economy Project today released a new analysis of home and small business lending in NYC, with a focus on the four banks that have historically held the largest share of NYC’s municipal deposits. The analysis found these four banks – Bank of America, Citibank, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo – responsible for egregious racial disparities in mortgage lending, as well as small business lending and branch distribution.

The analysis comes on the heels of a damning report from the NYS Attorney General exposing systemic

The city keeps a running list of “designated” banks (currently there are 28) approved to hold City funds, including billions in public deposits. New Economy Project analyzed loans and services provided by the four designated banks listed above.

According to the analysis:

- The banks originated just 25 cents in mortgage loans in neighborhoods of color for every dollar they lent in all other neighborhoods. That’s despite the fact that the number of NYC neighborhoods of color is roughly equal to the number of all other neighborhoods. Moreover, when looking at the number of loans made, the disparity between neighborhoods of color and other neighborhoods was almost the same: the banks made just 30 loans in neighborhoods of color for every 100 loans made in all other neighborhoods.

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, the banks failed to equitably distribute loans made available through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) for struggling small businesses. They provided only nineteen cents in PPP loans to small businesses in neighborhoods of color for every dollar in PPP loans made in all other zip codes.

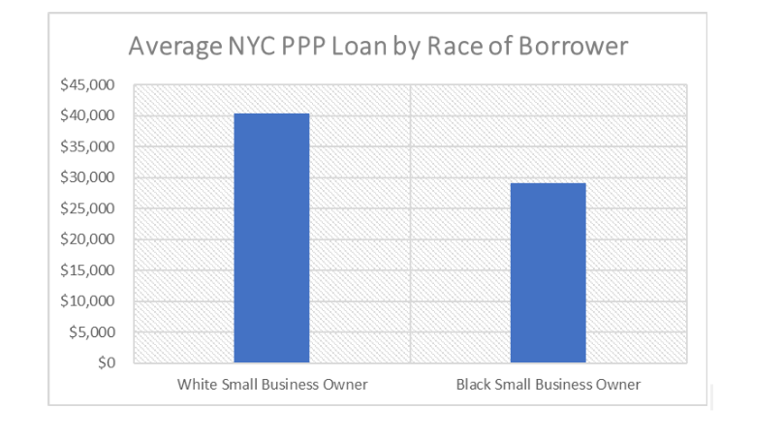

- When comparing borrowers who disclosed their race in PPP datasets, the banks lent 40% more loan dollars to white small business owners, on average, than to Black small business owners.

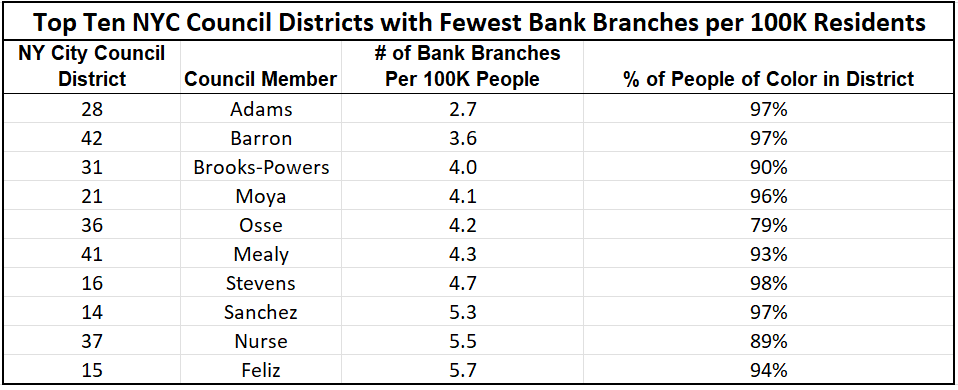

- New Economy Project also examined branch locations of all banks operating in NYC. In eight of the ten NYC Council districts with the fewest bank branches, 90% or more of residents were people of color; in all ten zip codes, at least 75% of residents were people of color. Wells Fargo, notably, has only one NYC bank branch outside of Manhattan.

See charts and methodology below.

In response to the analysis, the Public Bank NYC Coalition called on the City Council to pass the People’s Bank Act, a legislative package sponsored by Council Member Keith Powers that would mandate public transparency about the City’s finances and financial relationships, and lay the foundation for a municipal public bank.

“These findings once again make clear that the City must divest from the big banks as a matter of racial justice,” said Tousif Ahsan of New Economy Project, which coordinates the Public Bank NYC Coalition. “A public bank would allow us to do just that, and that’s why the NYC Council must pass the People’s Bank Act. Through public banking, the City can responsibly steward our public dollars while investing in permanently affordable housing, small and worker-owned businesses, community solar, and other community wealth-building initiatives in historically redlined Black and brown neighborhoods.”

In 2022, after the Public Bank NYC coalition called on the City to remove Wells Fargo’s designated status, citing the bank’s discrimination against Black homeowners, Mayor Eric Adams and Comptroller Brad Lander publicly promised to cut ties with Wells Fargo. Even so, the bank was reapproved for the City’s designated list this year.

The new data findings, however, show that all four of the top designated banks are perpetuating racial inequities – suggesting that the problem is not one “bad actor,” but rather the entire practice of placing the City’s funds in private banks, which are accountable to shareholders instead of the public.

New Economy Project’s analysis builds on the organization’s previous research and mapping exposing redlining and other patterns of lending discrimination in NYC, as well as a 2020 WBEZ Chicago investigation, which documented persistent racial disparities in Chicago’s home mortgage lending, and reports by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development that tracked racial disparities in the distribution of PPP loans during the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis also considered access to bank branches, which is much more than a matter of convenience for residents: previous studies have documented the importance of local branches to small business growth. Furthermore, in the absence of traditional banks, predatory lenders and high-cost financial services often fill the void, leading to massive wealth extraction from New York communities.

“Our credit union has a strong track record of serving communities of color,” said Linda Levy of the Lower East Side People’s Federal Credit Union. “By partnering with – and investing in – CDFIs, a public bank would increase our capacity to serve even more communities and provide funding to worker-owned businesses and MWBEs that have been ignored by the big banks.”

The NYC Council held a hearing on the People’s Bank Act in April of this year. Intros 499 and 498 would require the City to provide the public with a report of its accounts with designated banks, including balances and fees charged. The bills would bring much needed transparency and accountability to the city’s financial relationships and allow New Yorkers to assess the scale of City deposits available to a public bank. Resolution 203 calls on the state to enact the New York Public Banking Act (S1754/A3352), which would create a statewide regulatory framework for local public banking – making it easier for New York City and other local governments to establish public banks. Intro 999 would establish a NYC task force to create an implementation plan for a municipal public bank.

A July study conducted by the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School on the potential of public banking in New York City found that, in its first five years, a public bank would generate 70,600 local jobs, over 17,000 new or rehabilitated affordable housing units, and $5.8 billion in lending for community-wealth building initiatives in Black and brown communities – including about $2 billion for local small businesses, with a particular focus on MWBEs, and about half a billion dollars for new mortgages.

“For far too long, predatory lenders have preyed on East New York homeowners and tenants,” said Debra Ack, a founding member of East New York Community Land Trust. “Meanwhile, the big banks are more interested in turning a profit than in ensuring Black and brown young people have access to truly affordable housing and community wealth building opportunities. We need a public bank chartered to serve the public interest that will invest in real affordable housing in our communities of color.”

“As a founding member of the worker-owned business Hopewell Care Childcare Cooperative, I am proud to be fighting for a world where people of color, single mothers, and immigrants have control of their working lives,” said Gale Johnson, a worker-owner of Hopewell Care Childcare Cooperative. “New York City should stop putting its money in big banks that neglect Black and brown-owned small businesses, especially worker-owned businesses like ours. The time for a public bank is now.”

“As a community organization mobilizing low-income people of color across the city, we continuously see people being priced out of communities in Brooklyn,” said Carlos Encarnacion, a Community Organizer with New York Communities for Change. “Establishing a public bank in New York City will be essential to fund much needed affordable housing for those who need it the most and who keep the city running – the working class.”

“It’s becoming abundantly clear that public banking is a solution to persistent redlining and discrimination that has plagued New York City for years,” said Jodie Leidecker, an Organizer at Cooper Square Committee. “We need to ensure that all New Yorkers have decent housing, a stable environment, and access to equal opportunities.”

SOURCES & METHODOLOGY

Bank Branch Analysis

Bank Branch address locations were obtained from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s annual Summary of Deposits dataset (June 2023) and aggregated by NYC Council Districts obtained from the NYC Department of City Planning.

Home Mortgage Lending Analysis

Statistics on mortgage loans use HMDA data obtained from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Data include all home purchase loans originated by Bank of America, Citibank, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo in NYC from 2018-2022. Data reported by census tract were aggregated into Neighborhood Tabulation Areas (NTAs) published by the NYC Department of City Planning, as was demographic information published by the U.S. Census Bureau (American Community Survey 2019 5-Year Estimates used for loan years 2018-2021, and American Community Survey 2021 5-Year Estimates used for loan year 2022). Neighborhoods of color are defined as those in which fewer than 30% of residents identified as non-Hispanic white.

PPP Loan Analysis

Statistics on the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) use PPP loan data obtained through the Small Business Administration website (PPP FOIA Loan data last updated October 3, 2023). PPP loans to small businesses are defined as loans up to $150,000. Loans were filtered by “Originating Lender” for JPMorgan Chase, Citibank, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo. The total loan amount per neighborhood was calculated by aggregating all the individual loans (“Current Approval Amounts”) by zip code.

Neighborhoods of color are defined as zip codes in which fewer than 30% of residents identified as non-Hispanic white, according to the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey 2020 data (accessed through CDX Technologies Zip Code Batch Reporting – State and County Data purchased on November 11, 2023). Non-residential zip codes were excluded from the analysis.

New Economy Project also divided the total loan amount per zip code by the number of registered businesses in each zip code. On a per business basis, small businesses in neighborhoods of color received less than half the total dollar amount of loans made to small businesses in other zip codes. Total number of registered businesses per zip code was obtained from CDX Technologies Zip Code Batch Reporting – State and County Data, purchased on November 11, 2023.

The analysis of PPP loan amounts by race was calculated by comparing the mean loan amounts made by Chase, Citibank, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo to borrowers who indicated their race as “White” (n=9,905) and “Black or African American” (n=1,671), as reported in the PPP FOIA Loan data. The race of the majority of borrowers listed in the data was not indicated.