Blog

November

2021

17

Public Banking for a Just Recovery: A How-To Guide for NYC

Posted by Andy Morrison

This piece was originally published by The New School’s Center for New York City Affairs

Recently, the New York City Board of Health passed a resolution directing the Health Department to work with other City agencies to eliminate systemic racism in policies relating to housing, economic opportunities, and other social determinants of health – key drivers of health inequities. “The Covid-19 pandemic must render unacceptable that which has been condoned for generations,” emphasized Health Commissioner Dave A. Chokshi.

As a new City government prepares to take office in January, it is fair to ask whether such words will translate into action. Will the next mayor and City Council do what is urgently needed to root out entrenched inequities, when doing so requires them to challenge Wall Street and other well-established interests?

One way to tell if they mean business is if they answer the call from dozens of community, labor, and cooperative groups to establish a municipal public bank.

A public bank is what its name suggests: A financial institution created and owned by the City, accountable to New Yorkers, and chartered to serve the public interest.

Public banking is common throughout the world. In many countries, public banks are advancing workers’ rights, investing in a renewable future, and responding quickly and effectively to the Covid-19 pandemic. In the U.S., the Bank of North Dakota has successfully financed public projects and made responsible loans to small businesses and others for more than a century.

New York City should put our public money to work for racial equity and a just recovery. Through public banking, the City can leverage its vast resources to support cooperative and community-led development – from permanently affordable housing to small and worker-owned businesses – in Black, brown, and immigrant neighborhoods hardest hit by Covid-19.

This year, the City will collect almost $100 billion in revenue from taxes, bond sale proceeds, Federal stimulus funds, and other sources. By law, the City must deposit all of it in commercial banks designated by the “NYC Banking Commission,” an obscure but powerful body composed of the mayor, City comptroller, and commissioner of the City Department of Finance.

In fact, a handful of the country’s biggest banks hold most City funds, with JPMorgan Chase holding the largest share. Banks pay modest interest rates on public deposits while exacting service fees and making money from “the float,” or the period between when funds are deposited and withdrawn. That means our public money is implicated in an array of ignoble bank activities – redlining, racial wealth extraction, and fossil fuel finance – that systematically harm people, communities, and the planet.

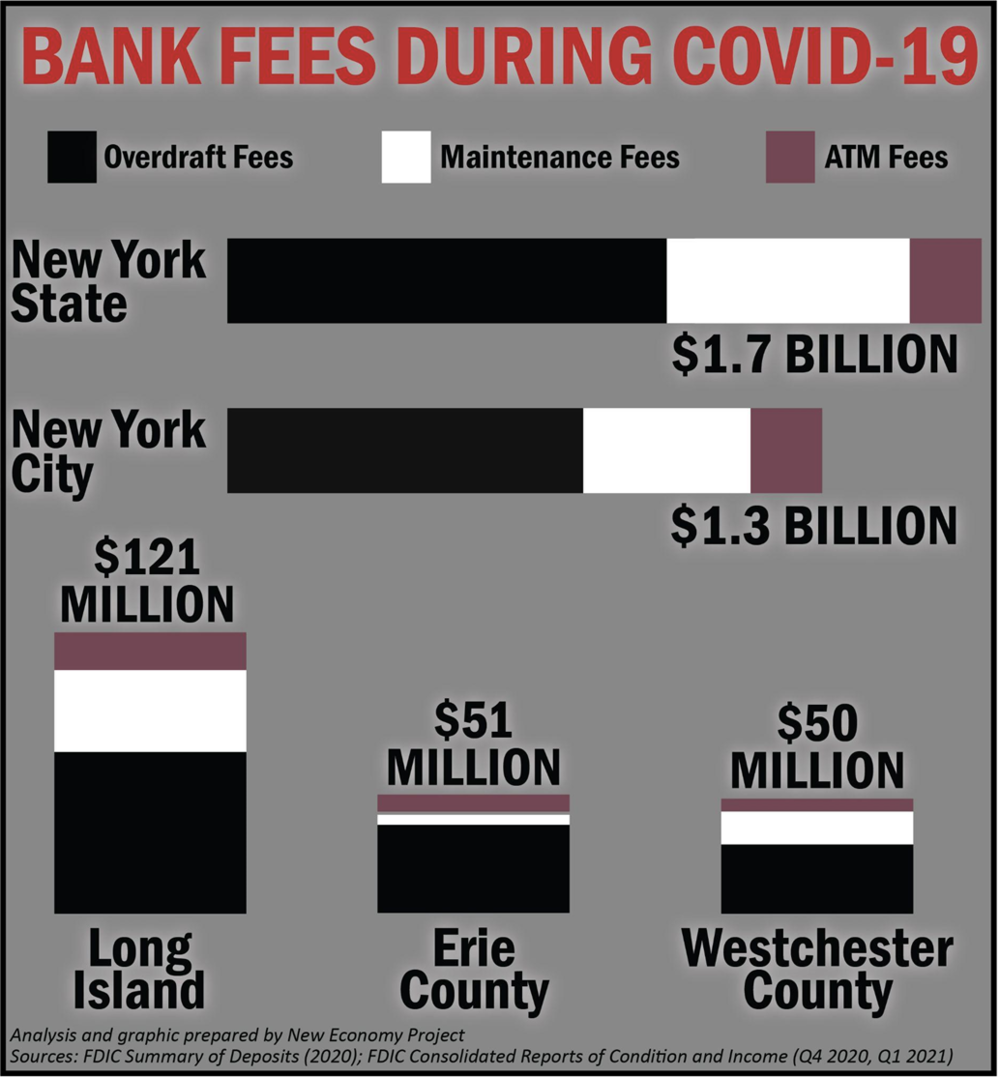

During the first year of the pandemic, for example, the City’s designated banks extracted $1.3 billion in fees from New Yorkers, according to research by the New Economy Project. Nearly two-thirds of this sum came from predatory overdraft fees, hitting banks’ lowest-income account holders. Chase was by far the worst offender, siphoning $1 billion from struggling New Yorkers.

Chase also has the dubious distinction of being the world’s leading funder of fossil fuels. The bank has pumped $316 billion into climate-destroying oil and gas companies since 2016.

It’s time New York City stopped placing public dollars in banks whose actions run counter to the City’s policy objectives on climate and economic inclusion. We need a public option – a bank for the people that will deepen public investment in democratically controlled initiatives that build community wealth. Here are two key steps.

First, pass “The People’s Bank Act” in the City Council. “The People’s Bank Act” is a legislative package that would lay critical groundwork for forming a municipal public bank in New York City and bring sorely needed transparency and accountability to the City’s banking relationships.

It is exceedingly difficult to obtain information about how much the City has on deposit with any of its designated banks, let alone the fees the banks charge or what they do with profits earned from our money.

What’s worse, the City’s process for designating banks is woefully unaccountable. Case in point: Last summer, the Banking Commission redesignated scandal-ridden Wells Fargo – a bank so corrupt U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren insists it should be broken up – to hold City deposits.

The People’s Bank Act would change that, increasing public participation in pivotal decisions regarding where the City banks and who benefits from our public money. It would also require the City to publicize a quarterly summary of its bank accounts, including balances and fees charged. Think of it as a bank statement for the people’s money.

The City should also start work on a business plan and articles of incorporation for a municipal bank. The Public Bank NYC coalition, which New Economy Project coordinates, is working with community development lenders, legal and regulatory experts, economists, and community-based organizations to advance an implementation plan for the City.

Second, pass the “New York Public Banking Act” in Albany. Under current State law, local governments seeking to establish public banks have no choice but to apply for a commercial bank charter, forcing them to fit into a model designed for private banks.

Enter the New York Public Banking Act, which would create an appropriate regulatory framework for local public banks. It would authorize the State’s financial regulator to issue special purpose public bank charters to cities and counties that demonstrate they have policies and procedures in place to ensure safety and soundness, public accountability, and ethical and responsible governance.

More than 100 organizations and dozens of State elected officials support the bill. Joining them is a growing number of mission-driven community development financial institutions (CDFIs) that see in public banking a game-changing opportunity to strengthen their work. By partnering – rather than competing – with CDFIs and other community-based lenders, a public bank would expand responsible banking services in historically redlined communities.

Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie should prioritize the bill and work with Governor Kathy Hochul to get it done in the 2022 legislative session.

In the face of multiple interlocking crises, from public health and housing insecurity to widening racial wealth inequality, we need bold action. If our elected officials are serious about addressing deeply rooted inequities that have been magnified by the pandemic, public banking should be at the top of their to-do lists in 2022.